One of the most interesting figures and artistic personas of the Polish emigrants’ milieu in London, where he resided from 1937. He produced both canvas and panel paintings, he drew and created various print, and also engaged in art criticism. He conducted a series of talks on art for the BBC, and also authored an essay series on English painters entitled From Hogarth to Bacon, and published in Warsaw in 1973.

Marek Żuławski came from a renown family, which bred numerous talents. He was the son of a philosopher, writer and translator Jerzy Żuławski (1874-1915), known for his Na srebrnym globie (On The Silver Globe) trilogy, as well as a cousin of the painter Jacek Żuławski (1907-1976), who was connected to the so-called Sopot school. The father of the latter, and an uncle to Marek, Zygmunt Żuławski (1880-1949) was a politician of the Polish Socialist Party, a social activist and deputy in the Sejm of the II Polish Republic. Marek’s brothers, Juliusz (1910-1999) and Wawrzyniec (1916-1957) also marked their names in the history of Polish culture – the former was a writer, poet and a translator of poetry, while the latter – a musicologist, composer and an alpinist. A love for the mountains, and later, a passion for the sea was shared by both Marek and Jacek. The second spouse of Marek Żuławski was the painter and sculptor Halina Korn-Żuławska, nee Korngold (1902-1978).

Marek Żuławski spent his childhood in Zakopane, he graduated from junior high school in Toruń. He took up the studies of painting at the Academy of Fine Art in Warsaw in 1926, simultaneously with his cousin Jacek. There, he studied under Felicjan Szczęsny Kowarki and Karol Tichy, and he obtained two diplomas – one in canvas and the other in panel painting.

In 1935 he set off on a trip across Western Europe, beginning a scholarship in France after a journey through Italy. Two years later, he settled in London, although he revisited France and Paris in 1947. Initially he was little known, but became more widely known after the war, as the author of a fresco in the Homes and Gardens pavilion of the 1951 British Festival. In 1958, his works garnered attention and acclaim after their exposition at the Religious Theme exhibit at the Tate Gallery. With time, he would expose works in known galleries across London more and more frequently. These events also constituted an occasion upon which Żuławski contributed to animating Polish immigrants in London. He was in friendly relations with the representatives of this milieu, Feliks Topolski and Marian Szyszko-Bohusz, as well as Tadeusz Piotr Potworowski, Halima Nałecz, and Franciszka and Stefan Themerson.

Regardless of the themes and motives taken up in his paintings, as well as the means he employed, one can say that the art he produced is concentrated on the human being, and clearly anthropocentric. The artist remained faithful to figurative art in the most obvious meaning of the term. In his autobiography, he wrote:

“Abstract art can never attract as strongly [as figurative art]”, and he also confessed the impression that “brutal” realism of a pre-columbian school of sculpture made on him, when he saw an exhibition at the Louvre in 1947: “I could not resist sketching some of the terracotta in my note pad that I always carry with me in my pocket.”

He was appalled by the “anti-humanism” of post-war French painting, in his memoirs, he concluded:

“Man deprived of the dignity he possessed in the Renaissance, or in the classicist period of the Enlightenment, ceased to constitute a theme for painting as such. If he does emerge, then it is an un-individual form, deprived of his recognisable traits, automated, or tortured.”

For Żuławski himself, the most important thing – as noted by Stanisław Frenkiel – was precisely

“(…) the dignity of man as a social being, man that fights and loves, man that is weighed down and prosecuted, whose archetype is Christ as a union of divine and human nature.”

The artist underscored that if not man exists for himself alone, then “the complete isolation of the artist isn’t possible”, either. He assigned responsible tasks to art, such as “one out of the [three – next to science and religion] ways of apprehending reality”, “an intuitive (…) search for truth about the world.” And Żuławski conceived of the artist as the one who possessed the ability of synthesising experiences, and the most credible witness of history. This is precisely why he trusted the representation, he wrote:

“The logic of pure painting leads straight to a canvas painted over smoothly with one colour. Such a painting fulfils a certain decorative function and can even be very pretty – but this diminishes the task that is art is supposed to perform.”

Even if at times Żuławski found a less sophisticated response to the question “what is art?”, in the end, he always returned to the essence of his convictions. In his biography, for example, we can read the following statement:

“If art is anything at all, apart from the biological function of certain individuals we call artists, then it is probably an attempt at organising chaos, in rebellion against reality.”

Żuławski was also preoccupied with mainly ethically or existentially engaged art, a fact which reflects his religiousness and the social views, shaped by his familial tradition. He usually sided with the weaker and depreciated (although at times he also took up lighter themes). Still, he rarely spoke directly, preferring the means of allusion. He referred to the Bible (Żuławski openly declared himself a Christian and often explored the passion in his works), as well as mythology in his search for the imagery that could constitute an ever pertinent metaphor of man’s struggle with fate. The several versions of Ecce Homo are exemplary of this motif, including the best known Ecce Homo II from 1958 and the Ecco Homo IV from 1961 (see also: the Susannah and Gilgamesh etching series from the 1970s). This area of his interest seems to have been shaped by his journey to Poland in 1946. Żuławski saw the ruins of Warsaw, he would recall that it was under the influence of this experience that he decided to focus of the “tragic, lost man in the state of prostration, in hope of a resurrection.” The aesthetics of his art was determined by a consecutive trip to Paris, in 1947:

“It was almost in rebellion against what I saw in Paris that I felt the desire to paint people as my main subject. Man was, after all, always the object of my greatest interest. An anonymous man, a disinherited and suffering man, astounded by everything that surrounds hims – a grey man of an equivocal gesture.”

One of the English art critics, Kenneth Coutts-Smith, wrote about Żuławski’s interest being

“(…) solely concentrated on man in his essential isolation, (…) imprisoned in his own skin… See the never-appeased wound of Being and Existence, the unsolvable conflict between man and man, between man and nature, and between man and God”.

In other texts, we can read that the figures depicted by Żuławski

“demonstrate the dignity of anonymous man, a victim of these inhuman times, wounded, but not belittled, filled with suffering, but not with despair”.

One of the most distinct examples of this kind of a composition is the Taking off the Cross (1946) where the artist painted a lonesome, somehow abandoned body of a man at the feet of the cross, stretched across a light rectangle of crumpled sheets and extended along the lower edge of the painting. The body, covered over with nothing more than a perisonium, is cut away against the background, which exposes the expressive character of the painting. Żuławski employed a dark contour here, known in the works Georges Rouault, with which he was fascinated at the time, and whom he considered to be one of the few „true religious painters of the 20th century).

“In principle, it is the Christ of Belsen. The crucifixion, i.e. the war has ended, but that which remains is a painful rag, an infinitely pained humanity. On the cross, the date reads 1945 A.D.”

The paintings Robotnicy przy stole (Workmen at a Table) comes from the same period (1947). It is composed much like the the Holy Trinity and evokes the renowned icon of Andrei Rublov. The figures – sketched out with a dark, fat line, with wrinkled faces – gather around a table which is captured from an elevated point of view. Stanisław Frenkiel wrote the following lines, when he dealt with the subject of such faces:

“In those post-war years, [Żuławski] went through a period of dramatic realism, with a tendency towards expression and towards bold forms with a strong contour. His painting leaned towards monumental forms, at times even hieratic ones, and ones that demanded huge surfaces – for which the walls of churches and spacious buildings constituted an ideal background.”

The artist did avow that he could better paint canvases of huge size, with figures of supernatural size (such as the Christ Among the Poor, from 1953), rather than small gouache paintings.

Still, one should not forget that the pre-war journey of Żuławski to Italy and France brought Żuławski “traces of the early phase of post-impressionist painting”. In practice, during the war and for a brief period after its end, this resulted in his liking of themes such as the landscape (Canal Near the Studio on Warwick Avenue, 1941), still life, a model (and at times a portrait) in an interior (Eileen Reading, 1944; Venus on Night Watch at the BBC, 1946), and a trust towards a very wide palette of colours with soft, blurred surfaces of tone that built an atmosphere of vagueness. He would grapple with this aesthetics, until he abandoned it altogether. During his long stay in Paris, he would ponder in front of the paintings of Bonnard and Vuillard:

“[…] perhaps I cannot digest anymore those aesthetic delicacies that took me so in the 30s”.

It was then, towards the end of the 1940s that Żuławski’s style consolidated and revealed a loose connection to the means known from paintings by Diego Rivera and Renato Guttuso. These means were somehow more subtle and filtered through the experience of exercises in colour.

“He painted with a wide gesture, and yet with moderation – devoting more attention to the general shape of the composition, than to the lay out of colours.”, as Frenkier rightly observed.

But he did treat colour in an autonomous way picked his tones without any fault – they were decided, clear, strong, and minimal. These traits, along with the way in which Żuławski used solid, statue-like forms of the bodies, modelled in a raw and simplified way, his way of accentuating the vertical axis of representation, the hieratic character of human figures and his amor vacui – a giving up of details that could disturb the composition’s expression all make for the monumental impression of his paintings. And if these works do incite associations with post-impressionism, it is mostly with its Polish school. In other words, it is with the canvases that depict Parisian interiors, decidedly framed views that expose a bold, “stein-glass” kind of contour, as well as with the paintings by Józef Czapski. For an example of this, see works of Żuławski such as Man Drinking Tea (1957), Man in Black Coat (1958), and Siesta (1959).

Interesting effects were also provided by the technical means that the artist employed. He often blended oil paint with varnish, which flowed over the canvas or the board and made the structure more thick. The body depicted with these means makes the impression of something more solid, more tangible, and red lacquer makes the depicted blood almost “literal”.

It is evocative of the paintings by Jean Dubuffet (Cain and Abel, from 1963, Adam Talking with God, The Dream About Flying, both from 1968, and Dead Man, from 1969). In the 1970s, Żuławski frequently used acrylic paint, which he mixed with the technique of collage. He would use a solid and intense colour, and simplified the synthetic modelling even further. He introduced sharped deformities of the human figure, he flattened both space and the blotches of colour, to finally come close to the aesthetics of Ron Kitaj’s New Figuration. The latter also settled in London at the time , but Żuławski painting’s do not have the same sharpness as those of Kitaj. In the 1970s, they take on more of a decorative character but at the same time, against the artist’s intentions, they also loose some of their inner tension (Law and Order, Mediterranean Cruise, both from 1975), and only occasionally is it still preserved (Death at the Hospital from 1975).

Under the impact of the birth of his son Adam, in the last years of Żuławski’s life his art quietens down and brightens its colours. The painter begins to discover the beauty of the world. At the same time, his faith gains power and this leads to a more frequent depiction of religious motifs as well as works commissioned by the Church (such as the monumental Baptism of Christ for Our Lady’s Church in St. John’s Wood in London, which was presented with the Friar Albert Award in 1982). In 1981, Żuławski painted a series of landscapes from this journeys to the Holy Land. Numerous sketches and drawings also form part of his heritage, including those that document the wartime destruction of Warsaw (1946), and pre-war journey across Western Europe. Later on, in comparison to these early, somewhat nervous and detailed works, his line takes on a more decided and tense character, in the many nudes he sketches in the 1970s. Some of the works of Marek Żuławski are kept at the Emmigration Archives of the Nicolas Copernicus University Library in Toruń, as well as the Tatra Museum in Zakopane.

In Poland, the artist is also renowned for his work as a critic and the author of a collection on English art (From Hogarth to Bacon), in which he pioneered introducing the works of Stanley Spencer to the Polish audience. He also wrote in detail about Francis Bacon, of whom previous publications in Polish did write, but not in great detail.

In the more recent past, the work of the Żuławski brothers was brought back to memory with the exhibition prepared by the National Museum in Gdańsk in 2002, entitled Marek and Jacek Żuławski. The life of Marek is recorded first and foremost in the memoirs he authored in his Study for a Self-Portrait, 1980.

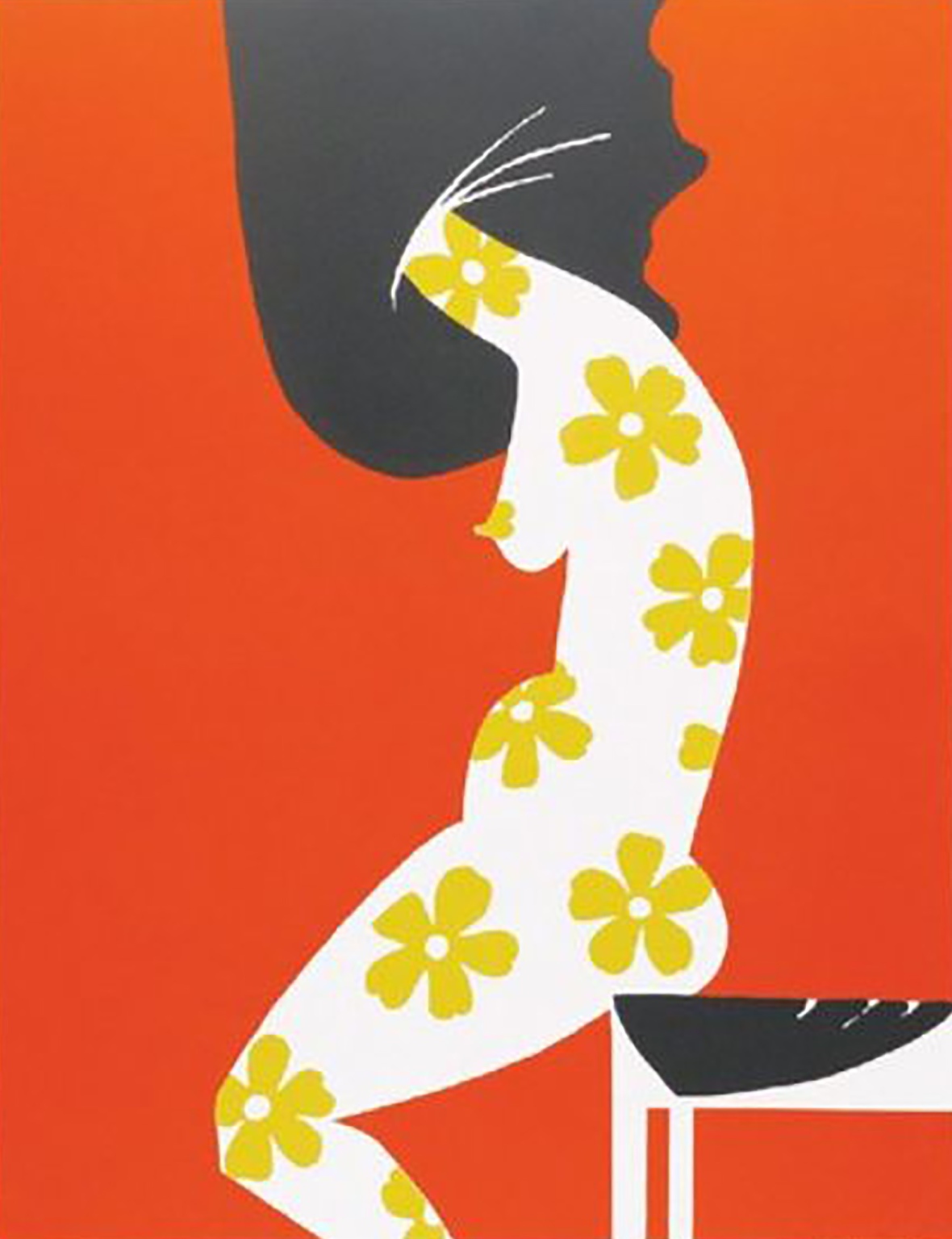

Maarek ZULAWSKI Girl Undressing on an Orange Ground

Marek ZULAWSKI Dancers

So interesting

LikeLike